From nappies to cricket: China’s Alibaba targets South Asia

Benjamin Parkin and Farhan Bokhari in Karachi and Ryan McMorrow in Beijing

In a vast warehouse on the arid outskirts of Pakistani megacity Karachi, hundreds of young workers sort through boxes of nappies, cooking oil and mobile phones.

The items are handpicked off the maze of shelves, carried by forklifts and ultimately packed into trucks to be dispatched to Karachi’s roughly 20 million residents and beyond.

Though Alibaba’s name and orange logo are not visible, this warehouse is a central part of the Chinese tech giant’s strategy to crack South Asia, one of the world’s fastest-growing e-commerce markets.

Daraz, an e-commerce company that Alibaba acquired in 2018, has proved a promising avenue into a tricky region for the Hangzhou-based company, which has effectively been shut out of India after the country curtailed Chinese investment over geopolitical tensions.

Through Daraz, Alibaba has expanded its reach as the Pakistan-based group spread to Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Myanmar, becoming the region’s largest e-commerce company outside India.

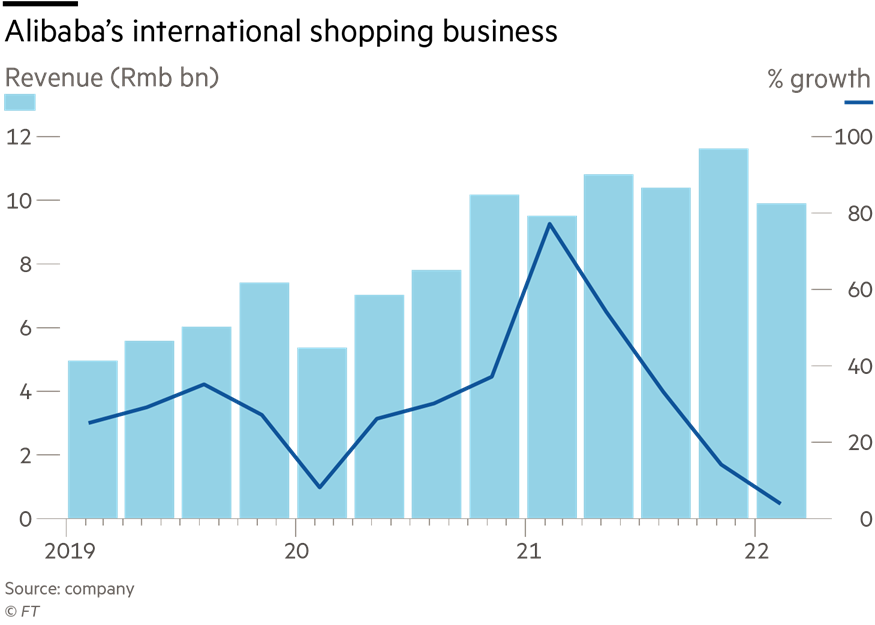

It comes as Alibaba steps up its global push. Its international business — including Daraz, south-east Asia’s Lazada, Trendyol in Turkey and AliExpress — is one of its more promising segments at a time when China’s tech crackdown, slowing economy and rising competition have left its domestic operations sputtering.

Chief executive Daniel Zhang told investors in December that the international business had “huge potential” with a “long runway ahead of us”. This year, new finance chief Toby Xu said it was one of two segments expected to become “increasingly important growth drivers in the future”.

Daraz was founded in Pakistan by Germany’s Rocket Internet in 2012 and expanded around South Asia before being acquired by Alibaba for $194 million in 2018. The company, which says it has about 40 million users, is primarily an e-commerce marketplace for small vendors but has expanded into lending and even streams cricket matches.

Bjarke Mikkelsen, Daraz’s chief executive, said the company was “just at the beginning”.

“By integrating [with Alibaba’s] ecosystem there’s a huge opportunity,” he added.

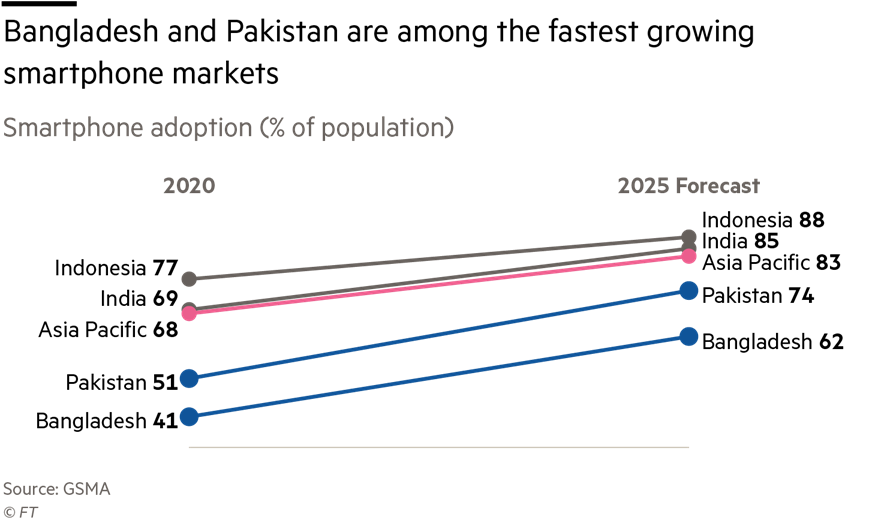

Daraz operates in one of the world’s most populous regions, with about 440 million people across its markets. Tech adoption is growing rapidly. For example, smartphone take-up in Pakistan and Bangladesh is set to grow faster than in other large Asian markets such as India or Indonesia.

“Pakistan was being looked at as a very unstable market,” said Jehan Ara, a Pakistan-based tech and software executive, but she added that it was now among the last sizeable untapped opportunities. “This is the largest market that’s left.”

Before he stepped down in 2019, billionaire chair Jack Ma envisioned making Alibaba “a platform for global small business”, acquiring Lazada, Trendyol and Daraz and expanding homegrown cross-border platform AliExpress.

The addition of the three local players deepened Alibaba’s position in three separate emerging markets, while AliExpress shipped cheap Chinese goods globally and spearheaded its European push.

But after Ma, a new generation of more inward-looking leaders took over and the international business — which contributed only about 7 per cent of total revenue — became less of a priority, according to one person close to Alibaba’s overseas operations.

Now, the internal pendulum is swinging back towards international expansion. In December, Jiang Fan, one of Alibaba’s most promising young managers, was handed control of a reorganised international division.

But the renewed global effort is likely to be rocky. Sales at Alibaba’s international division have been volatile and appear to be slowing after a boom during the Covid-19 pandemic. A 14 per cent growth in sales in the fourth quarter, compared with the previous year, dropped to a 4 per cent rise in the first three months of the year as the division was hit by Turkey’s inflation crisis and new taxes for packages shipped into the EU.

The growth of e-commerce and tech in countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh has lagged behind other markets including India and south-east Asia. While venture capitalists invested a record $366 million in Pakistani startups last year, for example, they invested $38.5 billion into neighbouring India, according to data from Pakistan’s Data Darbar and Bain & Company.

“Where India was in 2012, we’re here in 2022 . . . So we’re catching up, the change is happening, but the size is still very low,” said Mohammad Sohail, chief executive of Topline Securities brokerage in Karachi.

Daraz is one of the most visible examples of Chinese tech investment in a region where Beijing has spent tens of billions of dollars on infrastructure projects through its Belt and Road Initiative, but private sector follow-up has been slower.

“Generally our countries are very pro-China and they’re all in some shape or form part of One Belt, One Road,” Mikkelsen said. “Having a Chinese shareholder . . . has been seen as quite positive, that we’re attracting that kind of investment.”

While Daraz utilises Alibaba infrastructure such as Alipay for payments or Cainiao for logistics, executives said the company has also benefited from a more hands-off approach.

At Lazada, the largest of its overseas businesses, Alibaba parachuted in Chinese executives in a largely unsuccessful attempt to stave off competition from Singapore’s Shopee. But at Daraz and Trendyol, it left existing leaders in place. Mikkelsen, a former Goldman Sachs banker from Denmark, joined Daraz in 2015, before Alibaba’s acquisition.

While its foray into South Asia has proved promising, the short-term outlook has become more uncertain. Daraz’s markets have been particularly hard hit by global economic shocks. Sri Lanka became the first Asian country in more than two decades to default on its foreign debt last month amid an economic crisis, while Pakistan and Nepal have imposed import restrictions to try to control rising prices and dwindling foreign reserves.

The surge in fuel and other commodity prices has also pushed up Daraz’s costs. Some of its competitors, such as Lahore-based e-commerce company Airlift, have turned to mass lay-offs.

While Mikkelsen acknowledged that budget discussions with Alibaba’s leadership were “tougher this year than they have been for a while”, he argued that Daraz was better placed to withstand the storm — thanks to its deep-pocketed parent.

“E-commerce is sexy. It’s high growth. The money is pouring in in good times [but] sometimes people forget a little about the efficiency and path to profitability,” Mikkelsen said. “Alibaba is a long-term investor. Right now it’s a good time to have a strategic long-term investor with lots of cash.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.