3D printed hope: new limbs for Syrian refugees

When Ibrahim Mohammad started selling juice in the streets of Lebanon at the age 12 to support his family, he made $0.5 a day. Back then, he could have never imagined that ten years later, he would be competing for the one million dollar Hult Prize at one the most reputable entrepreneurship competitions in the world.

Mohammad is a stateless refugee from Palestinian origins who lived all his life in Lebanon. Raised in a refugee camp, Mohammad was faced with the harsh conditions of regular water and electricity cutoffs. Some days, after long trips to fetch water from neighbors, he had to walk miles to find a light spot for him to study or read a book.

“At this age, I was expecting someone to come over [to me] and not necessarily change the my whole situation, but at least offer the basics: water or electricity,” Mohammad said.

“I kept waiting and waiting and no one ever came, until I realized that I have to become this person and change at least one factor of the equation.”

In 2013, Mohammad moved to the US with the help of Amideast Lebanon to study mechanical engineering at the University of Rochester (UofR). With his passion for serving and finding solutions, Mohammad is now in his senior year and also serving as the president of Engineers Without Borders at the UofR.

Two students battling against all odds

While in university, Mohammad became friends with Omar Soufan, a Syrian, born in Chicago and raised in Damascus. Mohammad and Soufan shared experiences from their past and a vision for the future.

“We wanted to impact as many lives as possible,” said Soufan in a talk at the UofR.

On one vacation back home, Soufan had to pass through Lebanon to his home country when he witnessed the horrible situation of the families living on the Syrian borders. According to Amnesty international, Lebanon is considered the second largest host globally for Syrian refugees with over one million Syrian refugees, 70 percent of which are living under the poverty line.

“One of the main life pillars for a refugee aside food and shelter is hope! If a refugee lost hope, they are left with nothing else to live on,” Mohammad said.

The two university students then made it their personal mission to give hope to refugee communities.

“After thinking of refugees, we started thinking of who the most distressed communities are, and the answer was Syrian refugees,” Mohammad said.

“We wanted to get one more step deeper so we thought of Syrian refugee amputees because their disability makes them unwelcome guests, even among the refugee community due the inability to work or being a burden to their families,” he added.

In August 2015, Mohammad and Soufan started a rehabilitation clinic in Lebanon near the Syrian border to help the injured with prosthetics and physiotherapy. Soufan contacted the Syrian American Medical Society and partnered with them to get the prosthetics. They were able to crowdfund $7000 to kickstart the clinic. They now treat close to 300 patients per month and are still looking forward to more.

3D printed hope

During his vacation in Lebanon, Soufan noticed a huge need for upper limb prosthetics.

“When it comes to upper limbs, you can’t give the patient a wooden or metal stick as a substitute. It has to be a functioning limb to at least hold something,” Mohammad said.

“Additionally, the available limbs are not affordable and highly inefficient,” he added.

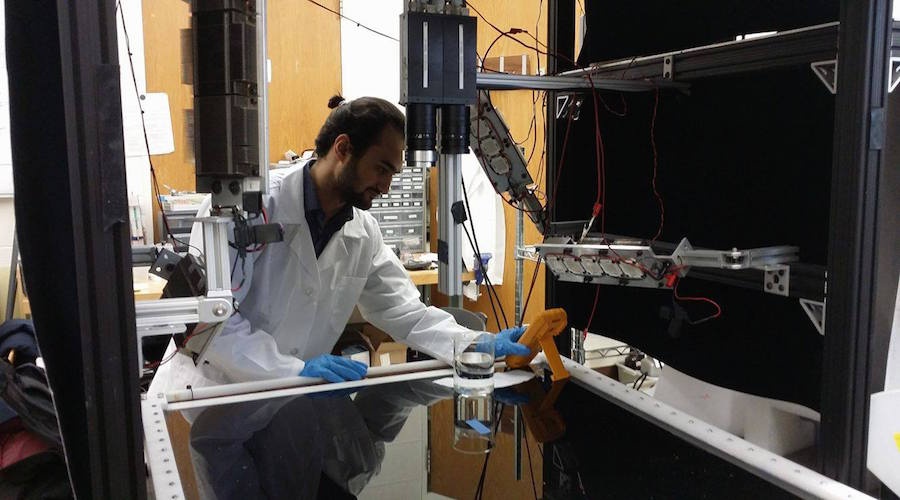

They reached out to professor Adam Arabian at Seattle Pacific University who now acts as their advisor on their ‘Prosthesis for a New Syria’ initiative that develops 3D printed limbs that are both mechanical and recyclable.

Their competitive edge is that the limbs are made of a flexible material, rather than a solid one, can be made to resemble skin color, is light, and is more affordable coming in at a cost of less $100, rather than paying $2000, a common market price for prosthetics on the market.

They are planning to offer the limbs to citizens who can pay for it and then use the profits to provide 3D printed limbs completely for free for amputee refugees.

“We are working now on optimizing the tension mechanism of the limb to improve its functionality. Our end goal is to have a mobile facility, a truck with three devices and one human being. All we will need in the truck is a computer, UPS, 3D scanner and a 3D printer. We drive to amputees, scan the limb, mold a socket, print the limb and fit the limb,” Mohammad said.

Soufan spoke of their implementation plan last summer to test the prototype on 15 patients.

Unfortunately, during his trip to Lebanon, he faced a lot of challenges moving the equipment from the US to Lebanon. The devices got stuck at the customs and one machine was completely damaged, delayed their implementation plan.

They are now working with one patient to get a 3D printed limb and in turn, receive regular feedback about the functionality.

They recently launched their crowdfunding campaign, partnered with the Qatari Red Crescent, to pay for their research and are working on their business model.

Challenges and future aspirations

“Not good” was Mohammad’s response when asked about the recent US executive orders banning Muslims from seven different countries from entering the US.

Mohammad told Wamda that he spent five days in his room depressed, wondering about what’s coming next to refugees like him. As a Muslim and a stateless refugee, he had doubts about leaving the US and not being able to get back in.

Mohammad is not from the seven banned countries, however, he doesn’t know what could happen to a student without a passport, but rather a refugee with a travel document.

Mohammad, Soufan, and two other colleagues are competing at the Hult Prize regionals this March in Silicon Valley. With their mission to spread hope, the team’s idea was to offer easily built houses for refugees that are made of recyclable material that is non-hazardous and inflammable.

“I hope to start a social enterprise that uses technology to empower refugee communities,” said Mohammad about his future aspirations.

“I hope that the society and the public would address the roots of the problem instead of offering short term solutions. I believe in the ripple effect and that everyone can help wherever they are … My favorite personal motto is: everything seems impossible until it’s done then it becomes inevitable.”