CycleHack gets the wheels turning for a more bike-friendly Beirut

Public Interest Design cofounder Ibrahim Zahreddine discusses the challenges of cycling in Beirut at Beirut CycleHack. (Image via Maysaa Ajjan)

Dog droppings, speeding cars and places to lock their bikes - these are just some of the hassles that cyclists face as they navigate Beirut’s traffic-choked streets.

But these issues didn’t seem to deter the cycling enthusiasts at the recent Beirut edition of CycleHack, an initiative that takes place in 35 cities around the world. They gathered at the three-day UK Lebanon Tech Hub-organised event to brainstorm ideas that could make Beirut more cycle-friendly and get people out on their bikes.

Are there cyclists in Beirut?

"What a lot of people don't realize is that the cycling culture exists in Beirut," Walid Dagher, cofounder of Public Interest Design (PID) Levant, told CycleHackers. “Think of the merchants we saw during our childhood who cycled at Manara to sell 'Kaa'k', and how they profited from it."

While Beirut may not be cycling-friendly the way Amsterdam and Copenhagen are, CycleHack participants and organizers aim to make it so. A handful of startups want to help too.

“We would like to crowdfund ideas that give people more power on what means of transportation they choose,” said Layal Jebran, lead project manager of Zoomaal, which, along with Altcity and Cycling Circle, was one of the main partners of the event.

But why does this matter?

Reducing air pollution, boosting time efficiency, sustaining infrastructure and even boosting small business are just a few of the benefits of having a cycling culture in the city.

"There is simply no place for everyone to drive a car in the city," said Zeina Hawa, event organizer and PID member. "People need to figure out other means of transportation by cooperating with governmental authorities."

One good reason may be the huge cost-reduction and economic benefits of substituting cars with bicycles, as countries such as Denmark have proven.

Budding initiatives

Several cycling initiatives have sprung up in Lebanon over the last few years, with bike touring company Cycling Circle and cycle couriers Deghri Messengers leading the way.

Founded by Karim Sokhn, both ventures are proving that cycling is doable in Beirut, both as a business and as a means of transport, even if they had modest beginnings.

Another beautiful night ride in Beirut organized by Cycling Circle. (Image via Cycling Circle)

“It started in 2011 with a nightride of 12 people in Beirut,” Sokhn recalled. “Then in April 2012 we did the first bike ride from Jounieh to Batroun, and 130 cyclists came, with zero injuries. I felt that there was a need to take it to the next step.”

Sokhn then created a bicycle delivery business, Deghri, which has not only created “tens of jobs” for young people, but is also profitable.

“We started with about two delivery orders per week. Now, we have around 30 per day, and the project is growing ”

But what about accidents?

“We’ve had only one injury so far, and it was only because of a maintenance issue with the bike, not a car accident,” Sokhn said proudly.

A look back

"We think of Beirut as congested and noisy, but it wasn’t always like this," said Dagher.

He explained how the city's thoroughfares were mapped over time, from very small beginnings in 1825 - only a "400 by 700 square-meter town with fences around it" - to what it is today.

A train transit route was built in 1906, spanning three main lines of the city. Dagher said people built homes and schools around those lines, paving the way for an urban population.

After the car "was marketed as a savior" in the 1960s, transit lines were removed and bus lines established instead - a huge mistake according to the CycleHack speakers.

What followed was a "drastic increase in car ownership from 1964 till 1994", said Nabil Nakkash, a transport systems engineer for TEAM International. During that time the city more than doubled its car count from 50,000 to 111,000 (see below). "Yet the population wasn't growing due to immigration and other factors."

Needless to say, the number of vehicles on the road has since continued to increase.

The absence of cycling routes in Beirut is a big challenge to resolve, according to the speakers.

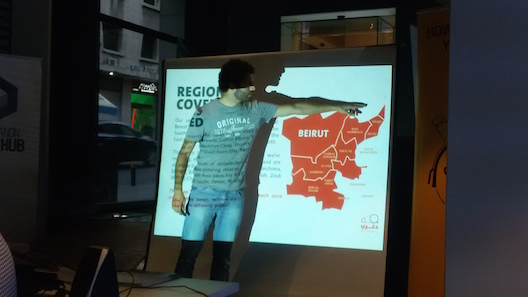

Deghri Messengers founder Karim Sokhn discusses his company's coverage area. (Image via Maysaa Ajjan)

But there are extra challenges that can be broadly classified in three categories:

Stakeholders and authorities

“The problem we have here is that it very hard to change policies because of lack of research, huge bureaucracy and a high rate of corruption,” said PID cofounder Ibrahim Zahreddine. “But that doesn’t mean that the intention of the government is to fight entrepreneurs, they need entrepreneurial ventures for economic growth.”

Dagher had a similar opinion. “We need to have contacts with municipalities and governmental authorities,” he said. “Our first problem in Beirut is that we think politicians are our enemies, and this is a losing battle. We need to be on good terms with these stakeholders. If you come with a certain logic, then they might actually accept.”

Public opinion

Sometimes, the people you are trying to help are the ones who stand in your way. While this initiative aims to improve public health and the city, a lack of technical knowledge is a considerable barrier but not one that's impossible to overcome.

“Its very important for people to understand that technology is involved in their everyday life,” said Lama Zaher, communication manager at UK Tech Hub. “Any real life problem like cycling or traffic can be tackled through innovative ideas. I think [people] are a bit intimidated by technology because it’s a language they don’t understand, and this is what we’re trying to solve in our capacity building programs.”

Other speakers seemed to echo Zaher’s thoughts.

“You need to have a receptive public for your idea to work,” Zahreddine said. “Gaining the critical mass is the most important thing.”

Culture of harassment and passiveness

“We live in a very cynical culture where people do not take initiative, and don’t follow the things that make a difference,” Zahreddine said. “So rallying them is a big challenge.”

Several speakers and contestants spoke of the harassment that cyclists face in the street.

“People think you’re crazy and that you’re risking you life if you cycle in the street,” Sokhn said. “But we’ve been operating for two years now and the number of deliveries we’ve made so far proves otherwise.”

CycleHack Beirut participants map the challenges, stakeholders and solutions for a more cycling-friendly Beirut. (Image via Maysaa Ajjan)

Potential solutions

Bhub team

Members: Habib Battah, Ahlam Jamal el Dine, Ilige Akiki, Alaa Almutawa, Charlotte Bishop

The first team wanted to create meeting places for cyclists that have posts to lock their bikes, charge their phones, get online and have a snack. “It’s a mixture of art installation and a community for cyclists who feel they are at home,” said a member. The team plans to create an app that maps the safe cycling spots in Beirut and allows users to share their location and comment on road traffic.

BYKE Team

Members: Nour Malaeb, Ibrahim El Kawam, Rita Harbie

The BYKE Team wants to create a cycling app that helps cyclists track distance, speed, calories, location and user interaction. Users can also record safe routes for other cyclists to follow.

“The value we're offering is that we want to make [cycling] a habit, not just a sport for the enthusiasts.”

Boober

Members: Masa Charara, Zeinah Hawa, Amer Mohtar, Nada Al-Qabili

Boober is a bike share system that operates like Uber. Registered users scan their app for the nearest bike, use it, and then park it wherever they wish, and pay for its use online. The bikes have sensors that allows users to locate them. Only registered users can “unlock” a bike. Prepaid cards are available for skeptics.

“If I’m in a hurry or have a one hour break, I can use this bike instead of taking my car and then getting stuck in traffic and not finding a parking space,” Hawa said. “I then can leave the bike without worrying about it.”